published 7/28/2025

TLS and QUIC: A Masochist’s Guide

I hope you’re having a great day. The sun is about to shine brighter. I was inspired by Helios himself to write about the riveting topic of TLS and QUIC.

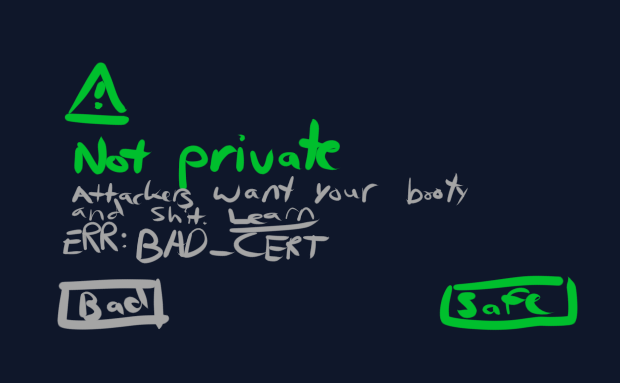

In my opinion, the most difficult part about QUIC is setting up a different protocol. QUIC requires TLS. There’s no way to disable encryption and only some clients let you circumvent certificate validation. If you screw it up, you’ll get a scary WARNING screen and users won’t be able to connect.

Most of this guide applies to HTTPS in general, which makes sense as HTTP/3 uses QUIC. WebTransport too as it’s layered on top of HTTP/3 but there are some important distinctions at the end…

tl;dr

- TLS authenticates who is allowed to serve

example.comvia certificates. - Root CAs issue certificates to those who can prove it via DNS.

- Cloud providers don’t support (non-HTTP/3) QUIC yet, ruling out the easy options.

- TLS is annoying for local development, especially for WebTransport.

About Me

I’m not a security engineer but I have dabbled in the low-level protocols.

For some unbeknownst reason, I’ve implemented both DTLS 1.2 (for WebRTC) and TLS 1.3 (for QUIC)… in Go.

Both were undoubtedly insecure but somehow passed the security audit and served production traffic at Twitch.

But then I left and those servers rightfully got the rm -rf treatment.

When in doubt, always refer to the nerds who take security seriously and use the correct terminology. I understand a lot of the security primitives but I don’t exactly have the LinkedIn Professional Certificates to back it up.

Why TLS?

Some boring background, feel free to skip ahead.

TLS is a client-server protocol that is used to verify the identity of the server (and optionally the client: mTLS) before establishing an encrypted connection.

When a client connects to example.com, the server transmits proof that it “owns” example.com.

This proof is in the form of a TLS certificate (technically X.509) which can be used to “sign” stuff by solving a math problem that is super super difficult without access to a “private key”.

TLS certificates can be used to sign other TLS certificates creating a “chain of trust”.

Without TLS, an attacker could intercept your traffic and pretend to be example.com to harvest your credentials, called a “man-in-the-middle” (MITM) attack.

Imagine if your router, ISP, or fellow coffee shop customer could pretend to be your bank.

Bad times ahead.

The fact that the private key is (virtually) unguessable is the only reason why I haven’t taken out a second mortgage in your name.

QUIC requires TLS 1.3. It’s good stuff, much better than TLS 1.2 in my opinion. There is no way to disable encryption but depending on the client, you can modify certificate validation. The IETF grey-beards decreed that the protocol can never be insecure, lest a lowly application developer shoot themselves in the foot.

- HTTP/3, WebTransport, and of course, Media over QUIC all use QUIC under the hood.

- HTTP/2 technically does not require TLS but browsers require it as a forcing function.

- HTTP/1 is the lone exception, allowing you to choose if you want to connect to

http://example.com(insecure) orhttps://example.com(TLS).

But even if you choose to use an insecure http:// connection, it prevents you from using newer browser APIs.

Want to notify a user when their Hot Pocket® has finished cooking?

Then you need to use HTTPS, lest your Hot Pocket® Tracker™ get compromised by a state actor.

So yeah, browser vendors don’t want you to make a security oopsie whoopsie and thus, effectively mandate TLS. Suck it up and let some cloud provider handle TLS for you… unless you’re one of the early birds using QUIC…

ominous foreshadowing

Certificate Validation

At a high level, a TLS connection is established via:

- The client connects to

example.comand sends aClientHello.- The client (usually) sends the domain via a SNI extension.

- The server transmits a

ServerHelloalong with a TLS certificate signed forexample.com.- The server uses SNI to choose the certificate if it hosts multiple websites.

- The client verifies that the TLS certificate is for

example.com.- It must have been signed by a “root CA”, or a certificate signed by a “root CA”, or a certificate signed by a certificate signed by a “root CA”…

What is a root CA? Your browser and operating system ship with a list of trusted entities that are authorized to issue certificates. It’s like having a list of approved locksmith companies that can make keys for any house. The list changes over time as these companies are audited or catastrophically compromised.

Fun fact, this is why you may have to explicitly apt update && apt install ca-certificates when setting up a Docker image.

Otherwise, if the base image contained certificate roots, it would get super stale.

One of the interesting things about TLS is that the client can choose how to verify the provided TLS certificate. There’s no requirement that you use these provided root CAs, or a root CA at all. You can make the protocol as secure/insecure as you want if you have enough control over the client.

So in order to run a QUIC server on the internet, you need to get access to a certificate signed for a specific domain name (or IP address).

If your server listens on example.com, then we need to prove to some root CA that you own example.com

Cloud Offerings

The easiest option unfortunately doesn’t work for QUIC. Poop.

Virtually every cloud provider offers HTTPS support often via their own root CA. You point your domain name at their load balancer and they procure a TLS certificate. But I glossed over something, there’s actually two parts to a “TLS certificate”: the private key and the certificate.

None of these services actually give you, the customer, the private key. Instead, they run a HTTPS or TLS load balancer that terminates TLS and proxies unencrypted traffic to your backend. It’s done for simplicity and security, they don’t want you having access to the keys.

This load balancing approach won’t work for QUIC until cloud providers start offering QUIC load balancers (one day). Welcome to UDP protocols; they’re barely supported on cloud platforms because TCP and HTTP is so widespread. At least there’s hope for QUIC support in the future because it powers HTTP/3.

LetsEncrypt

The recommended path is to use the glorious LetsEncrypt to get a certificate. It’s free, it’s painless, and it’s highly recommended by yours truly. There are paid offerings too, but there’s really not much point using them since LetsEncrypt became a thing.

How this works is that you need to somehow prove to LetsEncrypt that you own a specific domain and then they’ll give you a certificate valid for 90 days. “owning” a domain in this context means you control the ability to add DNS records. This could be in the form of an A record that points to an IP address you own or a TXT record with some token.

There are a few different challenge types:

- HTTP-01: Host a HTTP endpoint (insecure) that returns a specified token on the specified path. You own the domain if it points to your HTTP server.

- DNS-01: Create a DNS record with a specified token. You own the domain if you can create this TXT record. The server doesn’t even have to be running.

- TLS-ALPN-01: Host a TLS endpoint that returns a specified token during the TLS handshake. Same idea as HTTP-01, but more convenient for TLS load balancers.

This cert generation can be automated via certbot or any ACME library.

The main downside of LetsEncrypt is the 90 day expiration.

That means you actually have to be a good developer and worry about certificate rotations instead of punting it to future you.

That means adding a way to reload certificates, or periodically hitting the good old restart button.

ACME

It would be remiss of me to not mention that LetsEncrypt uses ACME v2.

You don’t need to use certbot and in fact you could integrate ACME directly into your workflow.

In fact, I’m using a terraform module to generate certificates for relay.quic.video.

It’s not recommended because if I forget to run terraform every so often, then oops, my certificate will expire and users can no longer connect to my server.

But it’s easy and it works for now so I’m embracing my folly.

I’d like to add ACME support within moq-relay itself to provision a TLS certificate on startup and automatically refresh it.

This makes it a lot easier to use cloud providers as you don’t need to fumble with background services (in Docker, ew) and reloading the server whenever a new certificate is generated.

The downside is being unable to generate wildcard certificates as those require DNS challenges.

Private Networks

Anyway, we’ve talked a lot about the internet, but what about the intranet?

The problem with a service like LetsEncrypt is that it requires our server to be public. What if we’re running our own private network or just developing an application locally? If LetsEncrypt can’t connect to our private network, then it can’t give us a TLS certificate.

Additionally, LetsEncrypt requires a domain name or a public IP. These aren’t expensive but it’s not something you can reasonably ask developers to purchase just to try running your code.

Remember when I said the client was responsible for verifying a certificate however it sees fit? If we control the QUIC client, then we can change that behavior.

NOTE: None of this currently applies to WebTransport as we don’t have enough control of the browser client. See the next section!

Disable Verification

The most obvious thing the client can do is skip verification altogether. There’s usually a DANGER warning associated and DANGER indeed.

If you skip certificate validation, your connection will still be encrypted but now it’s vulnerable to a MITM attack.

The server still has to present a certificate, but the client will blindly accept any certificate.

Even if it was generated nanoseconds ago, is riddled with typos, and claims to be porhnub.com: doesn’t matter.

moq-relay supports the —tls-disable-verify by jumping through a few hoops with rustls.

There’s similar flags in most CLI tools, like curl’s --insecure flag.

Custom Root CAs

Instead of using a “trusted” root CA that ships with the browser or operating system, we can use our own. It’s trivial to generate root CA which can then be used to sign certificates. No more depending on FAANG, we are our own auditor now.

openssl req -new -x509 -days 365 -nodes -out ca-cert.pem -keyout ca-key.pem -subj "/C=US/ST=CA/L=San Francisco/O=CoolCidsClub/OU=DaveLaptop/CN=cool.bro"This is arguably safer than using public roots because our own client can be configured to ONLY accept our root CA. It doesn’t matter if one of the many public CAs gets hacked as long as our root is kept under lock and key. But note that you’re now responsible for stuff like revoking certificates if you truly care about the securities.

The catch is that we need to configure clients to trust our root CA. This normally requires admin/root access, and can be done at an operating system or browser level. But you only have to do it once per root CA and then you’re golden.

This is the secret behind a tool like mkcert.

It’s a tool that allows you to use https in local development seemingly via black magic.

The first time you run it, mkcert generates a root CA and adds it to the system and browser’s trusted roots.

Afterwards, you can freely generate new leaf certificates on demand (without root) that are automatically trusted.

Custom roots are often used in enterprise and VPN software. When you install the VPN, or as part of a managed IT solution, it’ll include some root CAs for you to trust.

Side note: I highly recommend using private CAs and mTLS for service-to-service connections.

It’s about as dank as one can get when designing distributed systems.

There are cloud offerings available (AWS) and they actually give you the private key, so it works for QUIC.

Certificate Hashes

WebRTC also uses TLS (technically DTLS) even when establishing a peer-to-peer connection. How does this work?

Both peers generate a ECDSA certificate (or RSA I guess) and compute its SHA256 hash. They then send the hash as part of the SDP exchange to some secure middle-man (usually a HTTPS server). Yes, you do need a server even when establishing a peer-to-peer connection unless you’re a freak who exchanges TLS certificates via USB drive.

The peers draw straws and one of them assumes the role of the bottom server for the TLS handshake.

Both sides transmit a TLS certificate (mTLS) and verify that the hash matches the exchanged hash.

Ta-da, connection established, ignoring all of the ICE shenanigans.

The same approach can be used for QUIC both peer-to-peer and client-to-server. We’re effectively just trusting individual certificates (by hash) instead of a root CA. Just like root CAs, you need to secure the transfer of trusted certificates otherwise you’re vulnerable to MITM attacks.

Here’s some rustls configuration that validates certificates based on hash. It’s not the prettiest code but it works.

WebTransport

Unfortunately, Chrome’s implementation of WebTransport leaves a lot to be desired. Rant incoming, grab some popcorn.

NOTE: Firefox is spared from this rant because I haven’t tested it. Safari is spared because they haven’t implemented WebTransport yet…

Disable Certificate Validation

There’s a Chrome flag that apparently lets you disable certificate validation for WebTransport: chrome://flags/#webtransport-developer-mode

When enabled, removes the requirement that all certificates used for WebTransport over HTTP/3 are issued by a known certificate root. – Mac, Windows, Linux, ChromeOS, Android

If the description is to be trusted, this would mean disabling certificate validation on every website (that uses WebTransport) which is just a horrific thought.

This is the equivalent to silently disabling https on every website via a benign developer flag.

I sincerely hope that the description is just wrong and this only applies to localhost or something; somebody should test it.

If you’re having trouble with the TLS handshake then absolutely turn it on and don’t forget to turn it off afterwards. Not many sites use WebTransport right now but it would be super awkward when they do.

Custom Roots

Chrome currently doesn’t support custom root CAs for WebTransport. I’ve reported the issue multiple times to the WebTransport developer but it’s apparently by design?

It’s quite baffling, because you can use custom roots for HTTP/3 but not WebTransport… which uses HTTP/3. There’s literally no reason why it should use different certificate validation logic. Just call the same function!

I classify this as a bug because it rules out tools like mkcert.

Local development and private networks need to use another approach.

serverCertificateHashes

There was this awkward “Certificate Hashes” section earlier talking about WebRTC. That’s because WebTransport supports providing a list of certificate hashes for a similar approach.

Unfortunately, there are some strings attached. The certificates MUST be valid for less than 14 days and MUST use ECDSA. Apparently 2 weeks is the sweet spot between “secure” and “annoying as fuck”.

These are good restrictions so you can’t be lazy and ship the hash of some long-lived certificate with your application. However it means we absolutely need to figure out how to rotate certificates because 14 days is not a lot of time. Additionally, we need a secure mechanism to transmit our certificate hashes otherwise we’re the major of MITM town.

Private Networks

So what’s the best approach if you want to use WebTransport on localhost or private networks?

Unfortunately, I think serverCertificateHashes is the best (right now) as it doesn’t require users to configure their browser and disable TLS…

moq-relay listens on TCP and UDP (:443 by default).

- The server generates a TLS certificate on startup.

- The client fetches the certificate hash via a HTTP /certificate.sha256 endpoint.

- The client then connects to the WebTransport server using the provided hash.

When connecting to localhost, the certificate fetch can use good old HTTP.

But if you want to use WebTransport to connect to any other private network, oof.

The web server will need to use HTTPS to serve the certificate hash.

What this means is that you’re establishing a TLS connection just to establish another TLS connection. In fact, you could use an identical certificate for both the HTTPS and WebTransport connections. But now you have to deal with 14 day certificate rotations, all because Chrome doesn’t support custom root CAs.

It’s not a major problem once you figure it out. It’s just frustrating.

Finished

TLS is not too bad in production once you realize it’s all about proving that you own a domain. There’s a lot of existing tooling and resources out there.

But it’s a pain in the butt for non-public servers, as the whole “chain of trust” thing doesn’t work any longer. WebTransport makes life even more difficult. Please Mr Google, add support for custom root CAs already, it should be like a single line of code to reuse the same CAs as HTTP.

Want to commiserate about TLS pain? Join the MoQ Discord or even the rustls Discord.

Written by @kixelated.

![]()